Common assault charge

Common assault, also referred to as unlawful assault, can cause confusion due to its dual terminology. The Summary Offences Act 1966 uses the term “unlawfully assaulting” someone, while the relevant section is officially titled “common assault.” This distinction often leads to misunderstandings both in court and among the public.

Additionally, it’s important not to confuse common assault with “common law assault“, a more serious and indictable charge with a significantly higher maximum penalty. Some assault charges share the same basic elements but require an additional element, such as causing injury or serious injury, to be proven. Due to overlap between offences, police may lay multiple assault charges for a single incident, such as common assault, aggravated assault, or intentionally causing injury. Often, some charges will be withdrawn as alternatives.

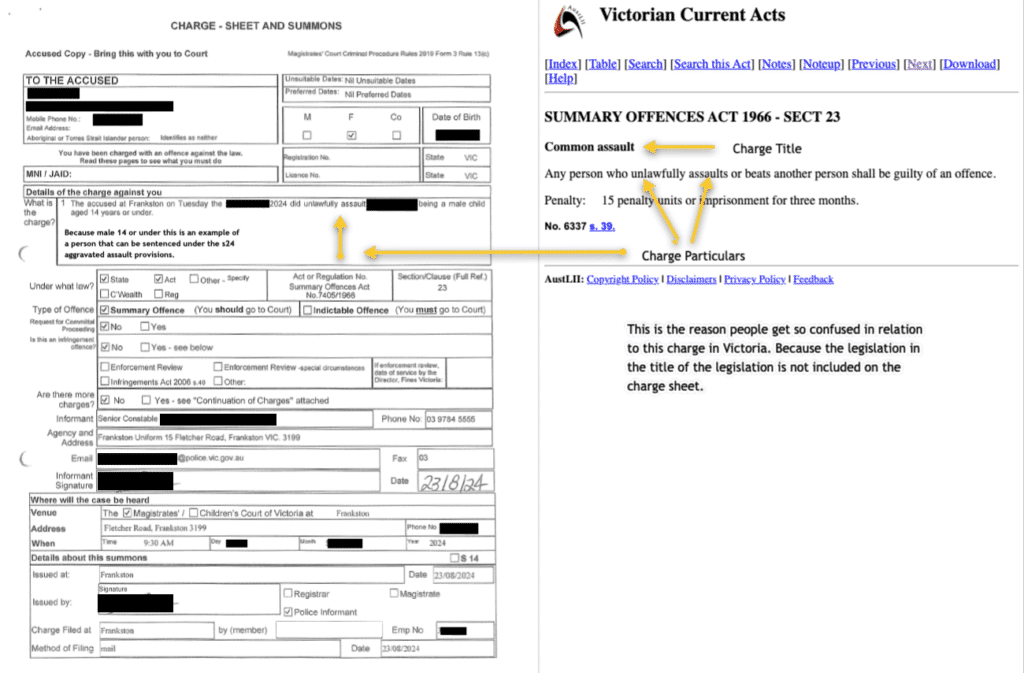

To determine what type of common assault charge you are facing in Victoria, look at your charge sheet, if you see reference under the legislation to the “Summary Offences Act 1966” and next to it see “s23”, then you are facing a summary offences common assault. We have provided an example of a charge sheet below.

Not all lawyers understand the nuances between the various assault charges. If you’ve been charged with common assault, it’s crucial to engage an assault lawyer who routinely handles these cases to secure the best outcome.

What is common assault?

In Victoria, common assault, also known as unlawful assault, occurs when someone intentionally or recklessly applies force to another person or causes them to fear that such force will be applied. The offence is criminalised under section 23 of the Summary Offences Act 1966. Common Assault carries a maximum of 3 months imprisonment or a fine of 15 Penalty Units.

The meaning of common assault is defined very broadly in the legislation, meaning you have to delve into the case law to understand how the charge is made out. Make sure you speak to a specialist criminal lawyer to understand the implications of common assault charges.

Common assault Victoria

Elements

The prosecution must prove the following elements beyond a reasonable doubt:

- The accused unlawfully assaulted or beat the complainant, that is:

- The accused applied force to the body of the complainant or caused the complainant to apprehend the immediate application of force to their body; and

- The accused intended their actions to cause such apprehension, or was reckless as to that outcome.

- The accused was aware the complainant was not consenting or might not be consenting; an

- The accused did so without lawful justification or excuse.

In relation to common assault, the offence may include a display of force or the application of force.

The mental element

- The prosecution must prove that the accused intentionally or recklessly caused another person to apprehend immediate and unlawful violence or intentionally applied force to another person (Fagan v Commissioner of Metropolitan Police [1969] 1 QB 439). This requires that the accused had hostile intent to cause fear or apprehension in the victim (R v Lamb [1967] 2 QB 981; [1967] 3 WLR 888; [1967] 2 All ER 1282).

- There will be no assault if touching was done merely to draw attention to something, without hostility or more force than necessary (Ashton v Jennings (1875) 2 Lev 133).

- The mental element will also be satisfied by recklessness if the accused was reckless as to whether a person was put in fear of unlawful violence as a probable result of their conduct.

Defence: Consent and lawful excuse

- If the force applied or displayed is lawful and consented to, there is no assault (Attorney-General’s Reference (No 6 of 1980) [1981] 1 QB 715; Re F (Mental Patient – Sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1 at 11–18, 27–32, 35–43).

- However, if bodily harm, or an “injury” (as defined in the Crimes Act 1958), is caused, consent is not a valid defence (R v Brown [1994] 1 AC 212; R v Stein (2007) 18 VR 376), as a person cannot generally consent to an indictable assault.

- An exception to assault exists in common law and in legislation for the lawful execution of the law, such as during a lawful arrest (De Moor v Davies [1999] VSC 416; Crimes Act 1958 ss 458, 459, 462A).

- Therefore, if an arrest is conducted unlawfully, an accused person is lawfully entitled to resist arrest (Director of Public Prosecutions v Hamilton [2011] VSC 598, 511-513).

Common assault examples

Application of force

- Any unlawful contact can amount to a common assault. The case law is very old and states as follows: That the slightest touch to another person with the necessary intent is sufficient force for the purposes of assault, no matter how slight the interference (Cole v Turner (1704) 90 ER 958).

- Even if the complainant is unaware of the force applied, the act may constitute an assault.

- Cutting the complainant’s hair without their consent, for example, is sufficient (Forde v Skinner (1834) C & P 239).

- Even spitting will constitute force sufficient to make out a common assault charge. In such cases, the charge will often contain the particulars that the “accused person assaulted the victim by spitting”.

- The act of “potting”, which is throwing or smearing faeces and or urine, can amount to assault (R v Veysey [2019] 4 WLR 137; [2019] EWCA Crim 1332).

- If the contact or force does not involve an intention to assault, however, such as touching someone to get their attention, there is no offence (Collins v Wilcock [1984] 1 WLR 1172). This is because, in such circumstances, there is a ‘lack of hostile intent’ (whether intentional or reckless) sufficient to satisfy the mental element of the offence.

- The takeaway here is that the force must have been applied with the necessary intent.

Apprehension of force

- For the complainant to apprehend unlawful force, it is necessary that the complainant perceives a present ability for the accused to apply force (Stephens v Myers (1830) 172 ER 735). However, it is not necessary that the complainant actually experience fear.

- Brandishing a firearm, even if unloaded and incapable of causing injury, may constitute an assault (R v St George (1840) 173 ER 921; 9 Car & P 483). If the complainant is unaware of the threat, such as if the firearm is pointed from behind, there is no assault (Police v Greaves [1964] NZLR 295).

- Words alone, and even silence, have been held to constitute an assault, such as a threat of harm made during a phone call, if the conduct is such to reasonably cause the complainant to perceive immediate physical conduct (R v Ireland [1998] AC 147). However, a verbal threat to inflict harm upon the complainant at a future time may not constitute an assault as the threat could not have apprehended immediate physical contact (Cruse v State of Victoria [2019] VSC 574; 59 VR 241 (Richards J)).

Lawful excuse case example

- An example of this principle of common law can be found in Kenlin v Gardiner [1967] 2 QB 510, in which the police did not have the power to detain a suspect with a view to determining whether or not the suspect should be arrested. In that case, two schoolboys were questioned by plainclothes police officers due to suspicions aroused by the boys’ actions as they visited various premises to remind teammates about an upcoming football match.

- When one boy attempted to flee and resisted by attacking the officer, and the other boy similarly struck a police officer who tried to detain him, both were initially convicted of assaulting a police constable in the execution of his duty under s 51(1) of the Police Act 1964. However, upon appeal, the Court of Queen’s Bench Division overturned the convictions, ruling that the police were not legally entitled to physically detain the boys merely to question them. The police had, therefore, committed an assault on the schoolboys, who were legitimate in acting in self-defence.

Common assault Crimes Act

- Common Assault does not exist in the Crimes Act 1958. In Victoria, common assault is found in the Summary Offences Act 1966. However, there are also different assault offences under the Crimes Act 1958 and at common law, which are indictable offences often requiring proof of actual injury or intent to cause harm.

- Adding complexity, the penalty for common law assault is specified in section 320 of the Crimes Act 1958, under the title common assault, but this refers to a distinct offence under the common law with a significantly higher maximum penalty of up to 5 years imprisonment.

Is common assault a summary offence?

- Yes, common assault is a summary offence and is the least serious of all the assault charges in Victoria. However, if bodily harm or an “injury” (as defined in the Crimes Act 1958) is sustained by the complainant, the accused is likely to face charges for a more serious and indictable offence such as;

Where will my case be heard?

- Common assault is generally dealt with in the Magistrates Court of Victoria unless the matter is heard together with indictable charges in the County Court or Supreme Court. The power to move the charge to those Courts exists under section 242 of the Criminal Procedure Act 2009 (Vic).

How serious is a common assault charge?

- In Victoria, common assault under the summary offences act is the least serious assault charge. It involves causing another person to fear immediate unlawful force or making minor, non-consensual physical contact, without requiring actual injury. The maximum penalty for common assault is three months imprisonment or a fine of up to 15 penalty units. As a summary offence, it will be dealt with in the Magistrates Court of Victoria.

However, if the assault results in bodily harm or an “injury” as defined under the Crimes Act 1958 (Vic), the accused may face indictable charges such as a causing injury offence. These are indictable offences punishable by much heavier penalties.

Common assault in circumstances of aggravation

- For aggravated forms of common assault involving the use of a weapon, involves kicking or occurs in the company of others or relates to a victim that is either a male child or a female, the Summary Offences Act 1966 provides for an aggravated assault.

Common assault penalty

The maximum penalty for common assault is 15 penalty units ($2963.85) or imprisonment for 3 months (Summary Offences Act 1966 s23). Aggravated Assault has a higher maximum penalty.

Penalties typically imposed for charges of common assault in Victoria (Sentencing Advisory Council):

- In the Magistrates’ Court, in the three years to 30 June 2023, the most common sentence for a charge a charge of common assault under the summary offences act, was imprisonment 40% of the time with other common sentencing outcomes in the Magistrates’ Court for unlawful assault including community corrections orders (22%), fines (15%) and adjourned undertakings (20%).

- As is always the case, sentencing outcomes are determined by many different factors and any predictive sentence should only be given in consultation with an experienced common assault lawyer.

How long does a common assault charge stay on your record?

- If you are found guilty and convicted of common assault, it will remain on your criminal record for ten years from the time of sentencing if you were 18 years or over when you were sentenced or five years from the time of sentencing if you were under 18 years.

- However, if the magistrate or judge is persuaded not to record a conviction about your matter, the conviction will become automatically ‘spent’ and will not be disclosed on a criminal record check (though this is subject to exceptions). See here for more on ‘what it means to have a non-conviction‘.

- Our common assault lawyers are experienced in helping clients avoid a criminal record. If avoiding a criminal record is important to you, engage one of our experienced criminal lawyers to assist you as soon as possible.

What to do next?

If you are facing common assault charges, don’t try to navigate this type of charge on your own. The impact of hiring a lawyer versus self representing can be profound, and potentially the difference between a criminal record, imprisonment or an acquittal.

There are several important questions to carefully consider with your lawyer before advising the court whether you intend to plead guilty or not guilty.

- Can the prosecution make out their case?

- Did you assault the victim and in what circumstances?

- What constitutes a common assault?

- Did you act alone, or was there a co-accused? This can aggravate the offence.

- Was there an injury? If so, more serious charges may apply.

- Have the police laid multiple charges in relation to the one incident?

- Do you have a defence? If you are pleading guilty, what can you do to minimise your sentence? A common defence in relation to unlawful assault is if you were defending yourself.

Preparation, time and careful planning are essential to achieve a favourable outcome, so call Dribbin & Brown Criminal Lawyers today.

Common assault legislation

Section 23 of the Summary Offences Act 1966

Common Assault:

Any person who unlawfully assaults or beats another person shall be guilty of an offence.

Penalty: 15 penalty units or imprisonment for three months.

Common Assault Lawyers