When a person is charged with a criminal offence, the prosecution bears the legal burden of proving ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ that the accused person is guilty. This is known as the criminal standard of proof and can be contrasted with the standard applied in civil cases (in which a plaintiff sues a defendant), which is on the ‘balance of probabilities’.

The high standard applied in criminal law is justified by the inherent imbalance in power between the state and the accused individual, as well as the serious consequences of a conviction, including imprisonment and other penalties. The prosecution’s responsibility to prove the elements of an offence beyond a reasonable doubt is essential to protect the rights of the accused, balance the interests of parties, ensure fairness and justice in criminal proceedings and uphold the integrity of the legal system.

A person charged with a criminal offence is presumed innocent until proven guilty under the law (Woolmington v DPP [1935] AC 462; Howe v R (1980) 32 ALR 478). This rule is a fundamental principle and cornerstone of the criminal justice system, enshrined in the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) s 25(1).

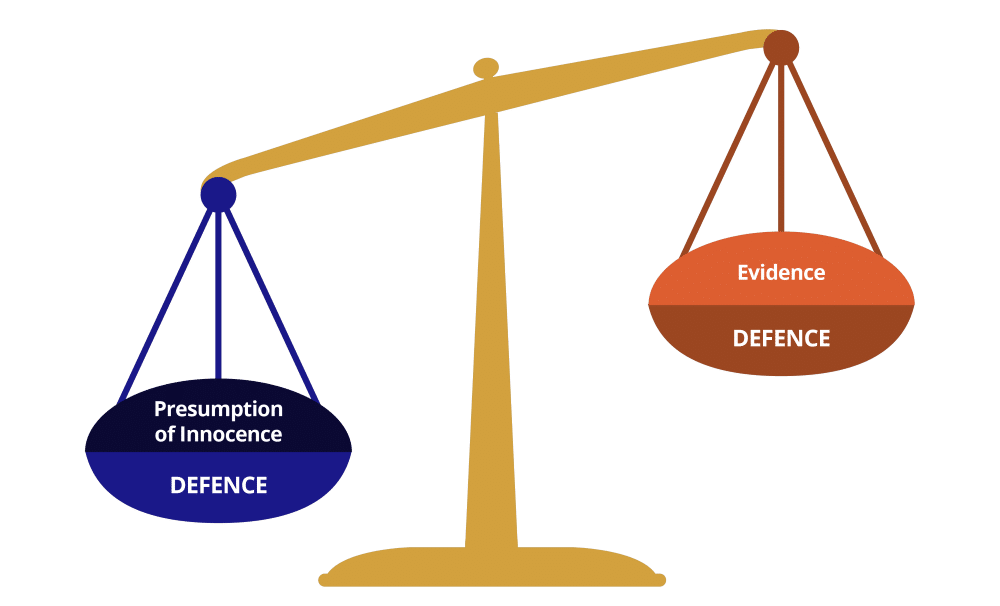

The defence is not required to prove the accused’s innocence; the accused is presumed innocent, and the prosecution must put arguments and adduce sufficient evidence that is sufficiently compelling to ‘tip the scales’ against the accused’s presumption of innocence in a criminal proceeding.

To discharge the legal burden of proof in criminal proceedings, the prosecution must adduce evidence that is admissible and credible. Such evidence may include testimonial evidence, physical evidence, documentary evidence or expert opinion. If the prosecution fails to meet the criminal standard of proof, the presumption of innocence is not rebutted, and the accused is entitled to an acquittal.

In a criminal trial, the requirement for the prosecution to prove the commission of an alleged offence beyond reasonable doubt is known as the burden of proof. Where legislation is silent as to who bears the burden of proof for an element of an offence, the law presumes that the onus of proof is on the prosecution (Chugg v Pacific Dunlop Ltd (1990) 170 CLR 249; Stingel v R (1990) 171 CLR 312).

This rule in criminal proceedings is stated by the House of Lords in Woolmington v Director of Public Prosecutions (1935) AC 462, at p 481-2, namely that:

The persuasive onus lies on the prosecution beyond reasonable doubt to prove all elements of an offence and to disprove all defences properly raised on the evidence (that is, to disprove all defences in respect of which the defendant has discharged his evidentiary onus).

As their Lordships also explained in Woolminton, the general rule is subject to two exceptions: the defence of insanity and any statutory exceptions. Whilst these observations were made in the context of civil proceedings, their applicability in criminal law has been confirmed by the High Court in Director of Public Prosecutions v United Telecasters Sydney Ltd at [18].

Notably, proof on the balance of probabilities also applies in criminal cases in specific circumstances, such as when the onus of proof is shifted to the accused (Evidence Act 2008 s141(2)) and when determining the court’s jurisdiction (Thompson v R (1989) 169 CLR 1; Ahern v R (1988) 165 CLR 87).

The rules on the onus of proof in criminal proceedings set out in the Evidence Act 2008 (Vic) s 141 are as follows:

If the onus is on the prosecution, the court is not to find the accused guilty unless it is satisfied that it has been proved beyond reasonable doubt (s 141(1));

If the onus is on the accused, the court is to find the case of the accused satisfied if it is satisfied on the balance of probabilities (s 141(2)).

This section codifies the common law position (for example, see Woolmington and Chamberlain v R (No 2) (1984) 153 CLR 521).

While the prosecution bears the burden of proving all elements to the criminal standard, the jury is not required to be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt of every fact relied upon by the prosecution to prove an element or to disprove a defence, so long as they are satisfied that the accused’s guilt has been proved beyond reasonable doubt (Jury Directions Act 2015 s61; Shepherd v R (1990) 170 CLR 573 per Dawson J).

The evidence is required to be considered together at the end of the trial, and one piece of evidence may resolve the jury’s doubts about another (Chamberlain). Therefore, if, after considering the whole of the evidence, the jury holds a reasonable doubt about the prosecution’s case, they must acquit the accused (Woolmington).

Unless otherwise indicated by statute, the prosecution also bears the burden of disproving any defence that arises as an issue in a trial (R v Youssef (1990) 59 A Crim R 1; Zecevic v DPP (1987) 162 CLR 645). This requirement arises if evidence or other material gives rise to that defence, and such a defence may arise from evidence or facts disclosed by either the defence or the prosecution.

Where a defence arises as an issue, where relevant, the prosecution must, therefore, prove that the accused’s offending conduct was not:

accidental;

involuntary;

a result of duress;

committed in self-defence (Crimes Act 1958 s322K);

committed as an honest and reasonable belief in the existence of facts which, if they had existed, would have been innocent (He Kaw Teh v R (1985) 157 CLR 523).

Consistent with the requirement that the prosecution must prove their case beyond a reasonable doubt, the jury must acquit the accused if the defence’s evidence gives rise to a reasonable doubt (De Silva v The Queen (2019) 94 ALJR 100, [11]; [2019] HCA 48).

For this reason, it is wrong to suggest to the jury that they are required to choose between the defence or the prosecution’s account. As the High Court noted in Murray v R (2002) 211 CLR 193, the issue for the jury is not whether it should accept the accused’s version but whether the prosecution has negatived it as a reasonable possibility.

According to the High Court’s decision in Green v R [1971] HCA 55: “A reasonable doubt is a doubt which the particular jury entertain in the circumstances. Jurymen themselves set the standard of what is reasonable in the circumstances.” Furthermore, a reasonable doubt means a doubt that is held by the jury as a whole, as opposed to a doubt that an individual juror may hold. In Green v R at p 15, the High Court recognised:

“[j]urymen themselves set the standard of what is reasonable in the circumstances. It is that ability which is attributed to them which is one of the virtues of our mode of trial: to their task of deciding facts they bring to bear their experience and judgment. They are both unaccustomed and not required to submit their processes of mind to objective analysis of the kind proposed in the language of the judge in this case. ‘It is not their task to analyse their own mental processes’: Windeyer J, Thomas v The Queen. A reasonable doubt which a jury may entertain is not to be confined to a ‘rational doubt’, or a ‘doubt founded on reason’ in the analytical sense…”

In all criminal trials, the judge must give the jury directions that the prosecution bears the onus of proof beyond reasonable doubt and that it is for the jury to determine whether this has been achieved (R v Neilan [1992] 1 VR 57). When explaining the term, the judge may:

refer to the presumption of innocence and the obligation of the prosecution to prove the accused’s guilt (Jury Directions Act 2015 s64(1)(a));

indicate that it is not sufficient for the protection to persuade the jury that the accused is probably or very likely to be guilty (Jury Directions Act 2015 s64(1)(b));

indicate that it is almost impossible to prove anything with absolute certainty when reconstructing past events and that the prosecution does not have to do so (Jury Directions Act s64(1)(c));

indicate that the jury cannot be satisfied of the accused’s guilt if the jury has a reasonable doubt about whether the accused is guilty (Jury Directions Act 2015 s64(1)(d));

indicate that a reasonable doubt is not an imaginary or fanciful doubt or an unrealistic possibility (Jury Directions Act 2015 s64(1)(e)).

If a defence is identified by counsel as a matter in issue under the Jury Directions Act 2015 s11, the judge must direct the jury that the prosecution also bears the onus of disproving the defence beyond reasonable doubt under that section.

A more challenging area arising in consideration of the standard of proof applied in criminal proceedings is understanding the evidential burden applied in cases where the prosecution seeks to rely on the existence of circumstantial evidence to support an inference of guilt.

A fact in issue can be proved with either direct or circumstantial evidence. This distinction relates to the way in which the evidence is to be used, such that if the jury must infer a particular fact from evidence, it will be circumstantial evidence.

Direct evidence: Evidence that directly proves a fact is called direct evidence and which does not require the jury to draw any inferences.

Indirect or circumstantial evidence: Evidence of a related fact from which the jury can infer the existence of the fact (Shepherd v The Queen (1990) 170 CLR 573).

The same evidence may, therefore, be direct and circumstantial depending on its use. For example, evidence given by a witness that they saw the accused holding a gun is direct evidence that the accused possessed a firearm and may also be used as circumstantial evidence that the accused killed someone with that gun.

Note that the term ‘direct evidence’ is also used to refer to testimonial evidence given by a witness of a matter for which they have personal knowledge (i.e. that they saw or heard).

Dawson J stated the generality of the requirement for the jury direction regarding circumstantial evidence in Shepherd (at 578), saying:

“The learned trial judge gave the customary direction that, where the jury relied upon circumstantial evidence, guilt should not only be a rational inference but should be the only rational inference that could be drawn from the circumstances: see Hodge’s Case (1838) 2 Lewin 227 (168 ER 1136); Peacock v. The King (1911) 13 CLR 619; Plomp v. The Queen (1963) 110 CLR 234. Whilst a direction of that kind is customarily given in cases turning upon circumstantial evidence, it is no more than an amplification of the rule that the prosecution must prove its case beyond reasonable doubt.”

Further to the above direction stated by Dawson J, it is usually necessary to give the following direction:

If, upon the whole of the evidence, there is any reasonable explanation which is consistent with the defendant’s innocence, the jury must find him or her not guilty (R v Hodge (1838) 2 Lewin 227; Mannella v R [2010] VSCA 357; Knight v R (1992) 175 CLR 495; Shepherd v The Queen (1990) 170 CLR 573; Chamberlain v R (No 2) (1984) 153 CLR 521; Barca v R (1975) 133 CLR 82; Plomp v R (1963) 110 CLR 234; Thomas v R (1960) 102 CLR 584).

Importantly, these directions arise from the general requirement that guilt must be proved beyond reasonable doubt in criminal matters and merely amplify the rule in cases of circumstantial evidence.

Search